It is December of 2002. The University of Portland women’s soccer team is in Austin, Texas, about to play Santa Clara for the NCAA championship. The Oregonian calls the team “more blue collar than showtime”; they’re known for their gritty defense, which has shut out every opponent so far, and their star striker, a sophomore out of Burnaby, British Columbia named Christine Sinclair, who has notched seven goals so far in the playoffs. They are a tight-knit group, punching well above their weight for a school of just over 3,000 students.

They have a rallying cry: win it for Clive. Their beloved coach, the 50-year-old Clive Charles, told the team he had cancer last spring. He’s getting treatment, but it’s a losing battle. In his thirteen seasons coaching the women, he’s come close to a championship several times, but never won, and his team knows this might be his last shot.

Here in Portland, a thousand or so students pile into the Chiles Center to watch the game on the big screen. UP students mingle with alumni and families; in one section, a pack of rowdy kids wearing only face paint and “kilts” (really a few yards of tartan fabric wrapped haphazardly around the waist) who call themselves the Villa Drum Squad pound drums and chant.

This is where women’s soccer as it exists in Portland today started to take shape. The scale is small, but you can catch a glimpse here of what Providence Park will look like 15 years in the future, just before a Thorns game kicks off—the drums, the tifos, the buzz in the air. At a school with no football team, in a city deeply unaccustomed to winning championships, Christine Sinclair is the biggest show in town.

This is the house that Clive built—without it, the Thorns wouldn’t be what they are—and in building it, he touched countless lives. Here’s how he did it, from the perspectives of three of those people.

1. Ganty

It is 1978, the Timbers’ fourth year in existence. Clive has just arrived in Portland. Soccer is still a novelty in the states, but the NASL is growing, with aging stars like Pelé, Franz Beckenbauer, and George Best drawing attention. Attendance for the Timbers has been respectable, with averages between 13,000 and 20,000 in their first three seasons.

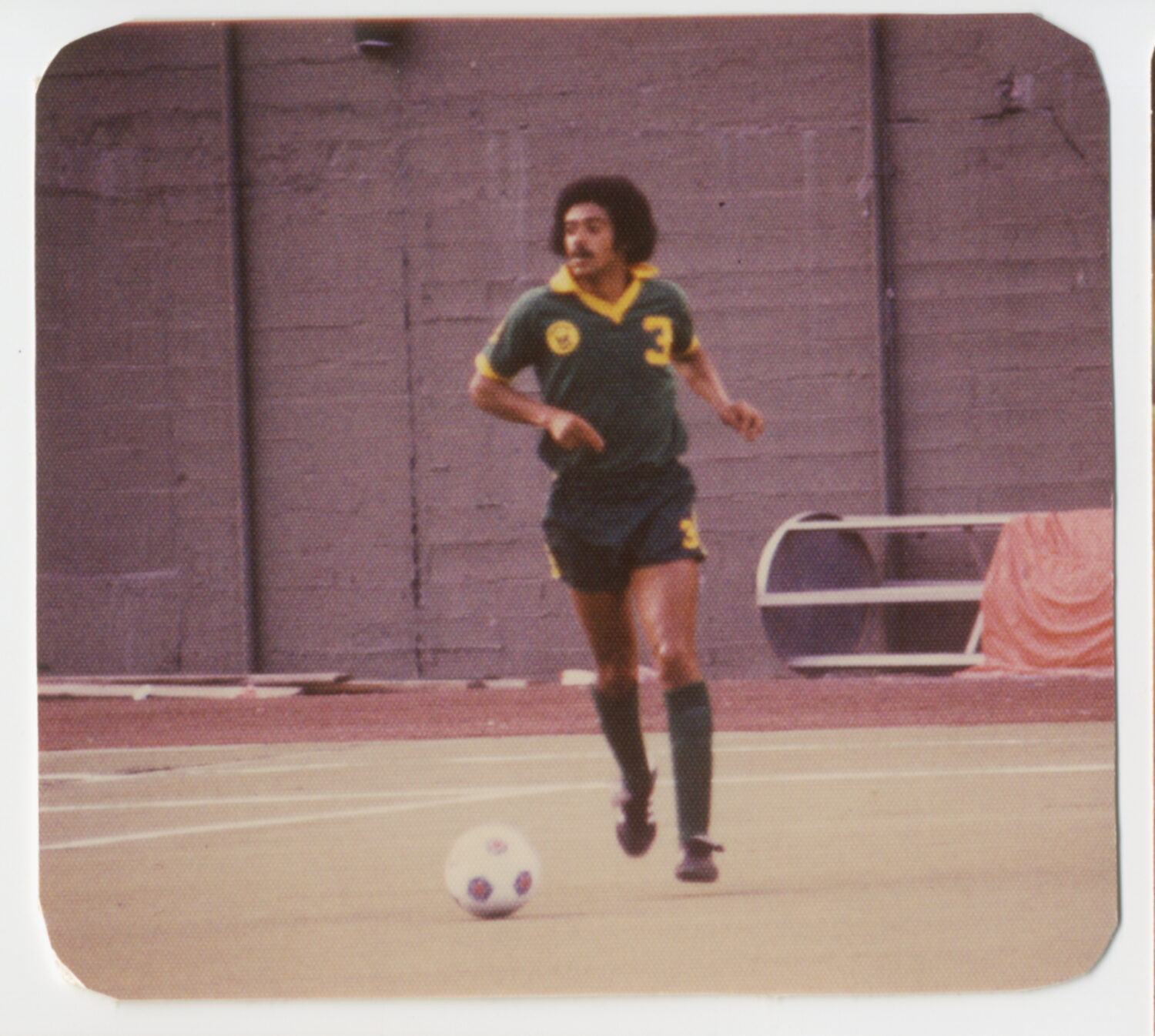

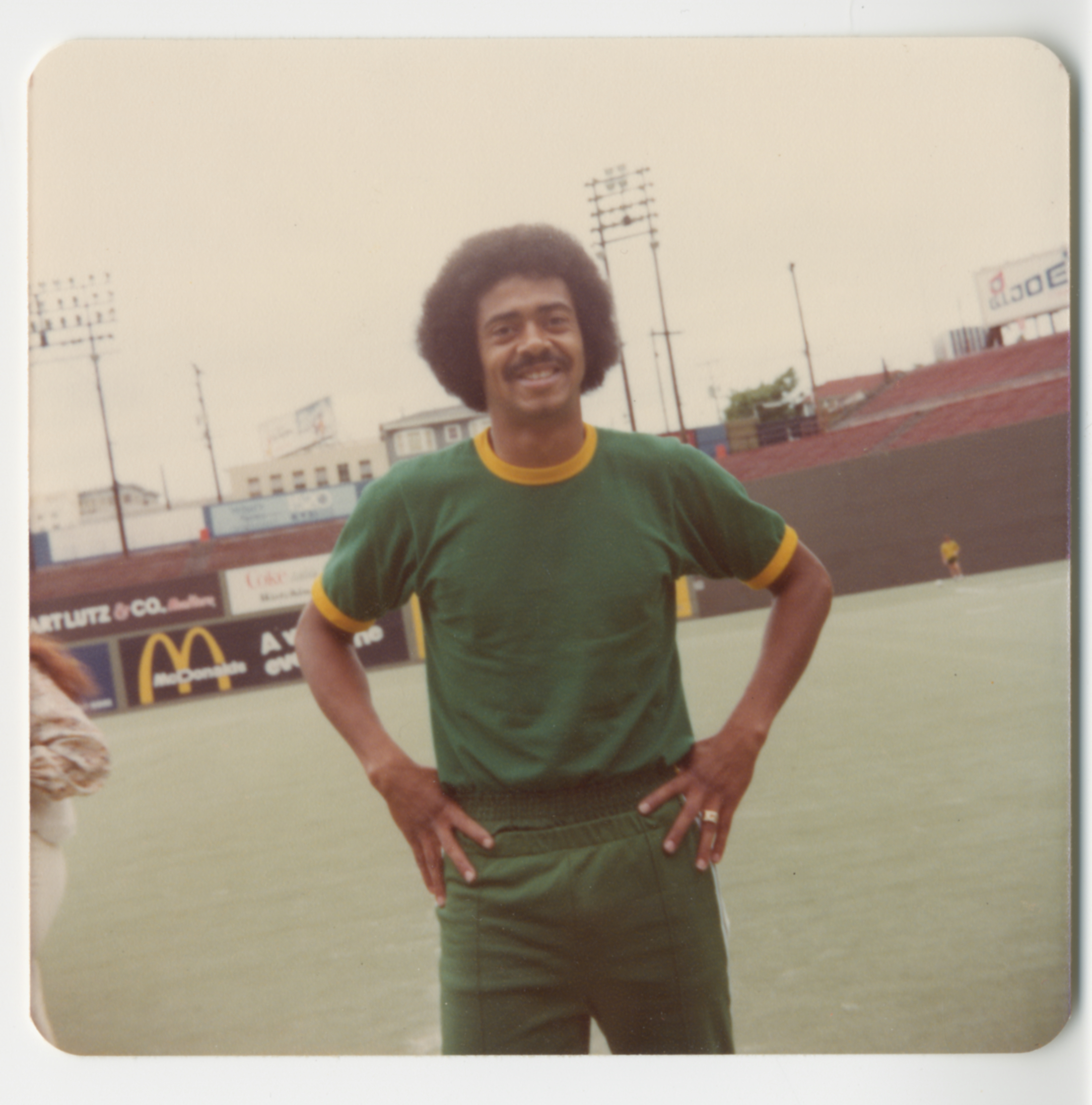

The club bought Clive from Cardiff City, where he had captained the team to promotion to the second tier. Brian Gant, a midfielder for the Timbers from 1977–1982—who is also, not coincidentally, Christine Sinclair’s uncle—describes Clive as “ahead of his time” as a player, an attacking outside back before attacking outside backs were really a thing.

“The back four back in those days, it was all about take no prisoners,” Gant says. “You had these all these big, strong physical guys, but he was a flair player who had a great left foot, incredible. He used to always tell guys, ‘hey, guys, I could play a tune on the piano with this left foot.’”

But it’s Clive the teammate, not Clive the player, who would really make an impression. That spring, when he walked into the Timbers’ dressing room at Catlin Gabel for the first time, the gravity shifted in his direction. “I thought, wow, he’s a friendly sort of guy, he is,” remembers Gant. “He was just the most easygoing, funny, just charismatic guy you’d ever meet.”

By that time, a substantial contingent of Timbers players were calling Portland home year-round. The club had already brought on Gant, Clyde Best, Willie Anderson, and John Bain. “The league itself was starting to become a lot more professional. And, you know, players were starting to come here, and Portland had a great reputation of being a good soccer city. The fans took care of us… the Timbers Army was started back then. And it was well looked at throughout the league, as well, as a great little soccer town.”

The team started to cohere, with Clive at its center. “Clive was the type of guy that was always talking and wanting to do things,” says Gant, who paints a picture of that time as a kind of summer camp. Much of the team lived in the same area in Beaverton, and they started going to lunch together every day. At lunch, they’d make plans for the rest of the day—golf if it was nice or pool if it wasn’t, always competitive. “Pretty soon, you had this whole group of guys that were all of a sudden not just connected on the soccer field, but connected off the soccer field.”

Clive called everyone by a nickname. Gant, who is tall and lanky, was Spider Man or Spidey, and eventually just Ganty; Clive himself was Charlo or Chazzy or the Dean of Divot, on the golf course. “We all knew it wasn’t to make fun of the person. It was to make that person feel special. Like, ‘oh, I got I got this title!’” He had that effect on people, of making them feel special.

There was no spotlight for an NASL player. The crowds weren’t huge, and many fans didn’t really understand the game. But they were enthusiastic, in part because Clive and his teammates spent time selling the game of soccer to the community. Clive could make friends with anybody, and the team as a whole was accessible on a level that’s unthinkable today. There were signings at Fred Meyer; after games, the team would go to the bar at the Hilton or the Benson and someone would invite them to their kid’s birthday, and they would actually go. “We’d show up at a party and say hi to the kids, play soccer with the kids in the backyard,” says Gant. “And you know, get a free meal.”

A few years later, like so many American leagues, the NASL went under. Clive spent the last few years of his career playing indoor soccer, which he reportedly hated, bouncing from Pittsburgh to LA. Eventually he and his wife Clarena came back to Portland, drawn by the growing soccer community the Timbers had sown. Back home, players of Clive’s caliber were a dime a dozen—and for a Black man, the outlook was especially poor. “He said, ‘Ganty, if I go back to England, all retired soccer players, all they want to do is open up a pub.’” He didn’t want that. He wanted to build something.

2. Tiffeny

It is the early 1980s. Clive is putting flyers under windshield wipers at a strip mall in Gresham.

Clive was a product of the West Ham academy, and he had a vision for Portland: a development pipeline from the youth level up through college, a place for local kids to get real training and grow into world-class talents.

But first he had to find the kids. So he and his fellow coaches, including Gant, would xerox a stack of pamphlets advertising a weekend- or week-long camp and pass them out all over town. Before long, they were booked for a whole summer, and Clive had secured a sponsorship from Fred Meyer.

It was at one of those camps that a particular kid, seven or eight years old, caught Clive’s attention. Tiffeny Milbrett was the only girl on the field, and Clive was transfixed. “He said, ‘oh my god, this kid is something else,’” remembers Gant. Their meeting was to set into motion a chain of events that ends with the Thorns becoming the best-supported women’s club in the world.

At that time, high-level women’s soccer basically didn’t exist. It wasn’t an NCAA sport until 1982; the first World Cup wouldn’t happen until 1991. Clive had grown up in a country whose governing body refused to sanction women’s competitions. But he didn’t bat an eye to see a girl dominating her age level.

“[That’s the] biggest thing with him, because even in this day and age,” says Milbrett, “there’s still plenty of men who don’t want to respect women in general, let alone respect women playing sports… I mean, we didn’t even have names for it back then, and he truly was a human being that, literally across the board, he was going to give the same respect and attention.”

He quickly became not just Milbrett’s coach, but a mentor and a role model. “He adored that kid,” says Gant, “ not only as a soccer player but as a person.”

Milbrett calls Clive “the most important male influence in my life. Most people probably just thought he was my coach, but he really influenced me in a very strong way through the game.”

From a young age, she was independent and confident, both on and off the field. Growing up with a single mom who had to leave for work early every day, she was often responsible for herself. “I think I’m very independent because of how I grew up,” Milbrett says. “And Clive really was one of the first top-level coaches that, it was ok to be a very, very strong, independent, confident woman. He was never, ever afraid of strong women. Ever. And you have far too many men, even the ones that say that their coach is 100% to the women’s side—I’m sorry, I experienced too many men that even in the women’s game, they can’t handle strong women.”

Where many coaches use their authority like a cudgel and feel threatened by questions or dissent, Clive saw Milbrett’s independence as an asset and nurtured it, helping her grow into the fearless goalscorer she became. “Tiffeny was the vision,” says Gant. “Clive said, I want a team full of those… that’s why he said, ‘we’ve got to have FC Portland, we’ve got to have that. We’ve got to develop these kids.’”

By 1987, he’d scrapped the clinics and started FC Portland, where Milbrett trained through the end of high school. By that point, Clive had been coaching the University of Portland men for a few years, and it was largely because of a desire to keep coaching Milbrett that he agreed to take over the women’s program, too.

UP was a small school, and Clive relied on his personality and his reputation as a coach, rather than the reputation of his program, to draw players. Anson Dorrance, who had helped push the NCAA to recognize women’s soccer as a collegiate sport, was drawing the vast majority of the top talent to North Carolina. “When Clive was picking players,” Gant says, “The first thing he did, he says, ‘I got to have quality character.’… so many of the girls that played for Clive that made the program so special were hard-working players. They’re good, honest citizens, good, honest students. They weren’t necessarily the best players throughout the country.”

Of course, there were exceptions, genuine world-class talents who came through UP. Milbrett was one; Shannon MacMillan, who Milbrett overlapped with, was another. Then there’s the GOAT herself.

3: Sinc

It is 2001. Christine Sinclair has just started at UP.

It wasn’t a coincidence that Sinc ended up in Portland. Clive had been a presence in her life before she was born. “My parents used to actually rent a house from him and Clarena up in Canada,” she told me a few years ago (Clarena is Canadian, and the couple had considered moving to Vancouver after Clive’s playing career). Clive didn’t just build women’s soccer in Portland, he built its most important player, kind of literally.

Sinc choosing UP was the natural outcome, but not just because her family knew Clive. As a shy 18-year-old, she needed a nurturing environment like his program. “I think I would have gotten lost in some of those bigger schools,” she said when she signed with the Thorns.

“She came here for the way [he mentored] people,” says Gant, “and because Sinc’s a pretty quiet kid, for the most part. She’s pretty quiet. And she was like that growing up.”

Sinc would probably have become a legend wherever she’d gone to college, but it’s less clear she would have become the kind of legend she is—the respected leader, the consummate teammate—without Clive’s influence. Clive was gregarious and charming where Sinc is quiet and thoughtful, but if you’ve heard Sinc’s teammates talk about her, listening to people who were close to Clive talk about him sounds familiar.

“It’s full and complete and total trust,” Milbrett says of him as a coach, “because first and foremost, he was just an outstanding human being to you. And that’s how you build up a player, that’s how you build up a person—building that kind of relationship through trust.”

Sinc could have gone to any school in the country. By her 18th birthday, she had already scored 21 goals for Canada, and she’d gotten a stack of scholarship offers. But she didn’t want to go to the most successful program; she wanted the coach who cared about her. “He was the only coach I talked to who was actually interested in me as a person,” she wrote in 2012. “For people who have ever been recruited, this is very unique.”

Clive would rib Sinc about her shyness, and soon she’d start teasing him back. As they got to know each other, she started to come out of her shell and speak up, where she’d usually stayed on the fringe when she was younger. “She toughened up a lot, coming to college,” Gant remembers. “You know, she learned to respect her voice. And she learned to communicate with teammates and coaches, and it really changed who she was as a person, I think.”

The Pilots went 16–3 Sinc’s freshman season and were eliminated in the College Cup semifinal by North Carolina. Sinc notched 23 goals, eight of them game winners. That spring, Clive called together “the Pilot soccer family, current and past players,” as Sinc wrote, and gave them the news: he’d been battling a rare form of prostate cancer for two years, after being diagnosed while coaching the US men at the 2000 Olympics. He intended to keep coaching, but nobody knew how much time he had left.

2002

The Pilots faithful, a few hundred strong in purple and white, greeted the team at the airport. They’d brought their drums along and chanted so loud the TSA agents couldn’t hear the metal detectors.

The team had been victorious in Austin; after they’d gone down 0–1 early in the second half, Sinc had leveled the score in the 61st minute, then scored the sudden-death game winner in overtime. Several players described a feeling that divine intervention was at work during the tournament. Clive said the win was “like a ten-ton weight has been lifted off me” and vowed not to let the trophy out of his sight. Supposedly he slept with it next to him that night.

Clive passed away in August of 2003. That championship win was the last game he ever coached. His players kept his memory alive, and the Pilots won another in 2005.

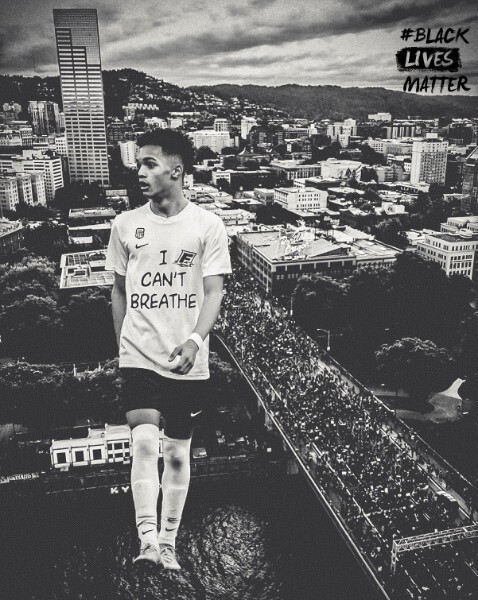

The kids and families and queer women who cheered the team on from the Chiles Center, many of them, would go on to form the Rose City Riveters. They’d learned how to love soccer at UP, and they helped show the world what support for a women’s club could look like.

Clive left an impression on everyone he ever met, and changed the lives of countless people he never did meet. His legacy goes way beyond this story. But it’s hard to overstate what he did for women’s soccer. The Riveters wouldn’t be what they are without UP, the Thorns wouldn’t be what they are without the Riveters, and the NWSL wouldn’t be what it is without the Thorns. None of it would have happened without Clive.

Sinc, of course, went on to become a giant in the game, planted firmly in Portland since her college days. Her dog is named Charlie in Clive’s honor.

After retiring in 2011, Milbrett started coaching, a career that took her to Colorado and Florida. Now she’s back on the Bluff, coaching on a part-time basis.

Gant stayed on at FC Portland, where he still works today. When he ponders where Clive might have been now, he suspects he would have moved on from coaching and taken an administrative job in the game. It’s easy to imagine him as the Thorns GM, or a league commissioner.

“He loved coaching,” says Gant. “But it was about the game, too. It was about, how far can we take this game? And I remember when he was coaching the [2000] Olympic team, he felt bad because it was time away from his UP kids and time away from Portland and Clarena and all that. But he says ‘Ganty, the game—it’s a global game now. It’s everywhere. It’s unbelievable.’ And you know, he’d just been diagnosed with cancer and everything. And it got emotional at times, because when he started talking about it, he sort of said, ‘and I might miss it.’”

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon