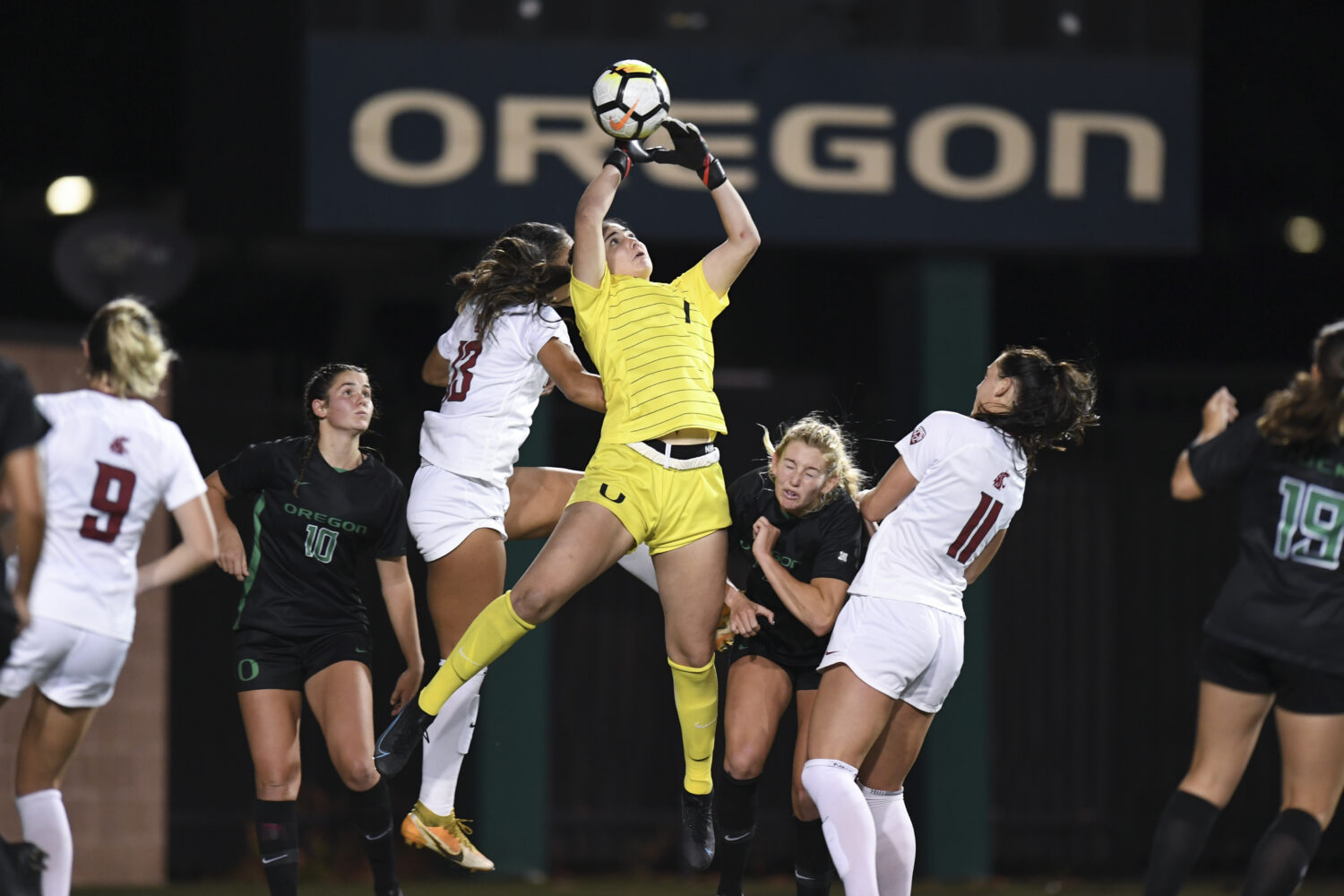

Goalkeeper Leah Freeman standing on her head and pulling out an explosive save to keep her team in a game became almost routine for the University of Oregon junior in her time in Eugene—even in a 2022 season that saw her miss games due to both COVID-19 and a red card suspension. Now, her collegiate career is entering a new era: In spite of a hip surgery in December 2022 to repair a torn labrum, Freeman has made the transfer to Duke University ahead of the 2023 college soccer season.

Moving across the country and working her way back onto the pitch is a tremendous change for anyone—especially for Freeman, who had never been to North Carolina before she signed with the team. But it’s been relatively smooth, all things considered, she says.

“It’s hard to be injured,” Freeman says. “It’s hard to come into a new environment injured. But I think everyone around me has done everything they can in their capabilities to make me feel comfortable and make me feel welcome.”

The transfer also puts Freeman in a position to compete for a national championship, as she joins a squad that made it to the quarterfinals of the 2022 NCAA Tournament.

“Leah is one of the top goalkeepers in the country,” Duke head coach Robbie Church said in a press release. “She is very good with her feet, is an excellent shot stopper and is good on crosses. Leah has been playing at a high level at Oregon and was one of the top goalkeepers in the Pac-12 over the last three years. She has tremendous experience and is going to be a really good addition to our goalkeeping core.”

Still, the loss of a starting keeper will hit the Ducks hard. “When we do the scout on Oregon before we play them, there’s a giant circle on Leah Freeman,” Cori Callahan, goalkeeper coach at University of California, Berkeley, told me during the 2022 fall soccer season. Callahan coached Freeman when she was growing up. “She’s the catalyst for that team,” Callahan says.

Freeman, originally from Berkeley, California, was a stalwart on the Ducks backline and off the pitch. In her three seasons at the UO, she set the school record for career shutouts and holds the record for lowest goals against average in program history. She was recognized for her goalkeeping prowess on November 8, when she was named Pac-12 goalkeeper of the year—the first Duck to win the honor.

Growing up in Berkeley played a big role in that. Freeman was able to watch collegiate women’s soccer powerhouses in the Cal and Stanford teams throughout her childhood. “She just had this fire and this enthusiasm for the game,” Callahan says. “She wanted to be great.” And that drive, alongside Freeman’s natural instincts, made her “a joy” for Callahan to train.

“At the right times, she made the right leaps and bounds,” Callahan says, alluding to Freeman’s private training and, later, the jump she made to join an elite club team in Danville, California, despite the commute. And having supportive parents didn’t hurt either.

So, Freeman made her way to Oregon. “I visited in May,” she says. “It was beautiful. The sun was out, and everything was really green”—a contrast from the less-forested landscape she was used to in the Bay Area.

Although Freeman was the first in her recruiting class to commit to the UO, then-club teammate Megan Rucker wound up joining her. The two were roommates beginning freshman year and grew especially close after living through the pandemic together. Rucker, in her words, “would literally do anything for that woman, as she would do for me.”

Despite Freeman and Rucker’s freshman year aligning with the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the two came into the team in a landmark year for a Ducks soccer program that was going through a rough patch. Their first season was also the first under UO head coach Graeme Abel, who had previously served as an assistant and goalkeeper coach on the USWNT.

“That class coming in and him coming in really lit a fire under us and showed us that we do have what it takes,” fifth-year Ducks midfielder Zoe Hasenauer says. “We can compete with anyone we need to.”

The Ducks proved as much that year when they beat Stanford, a perennial superstar in women’s college soccer, 2-1 their 2020 season in Freeman’s third match of her collegiate career. That same year, UO beat Cal at Berkeley—a personal success for Freeman in her hometown—and tallied 2-0 and 1-0 victories over Oregon State.

Freeman and her former team grew together from there, putting up back-to-back winning seasons in 2020 and 2021 for the first time in 40 years.

For Freeman, that development has also shown up in the expansion of her vocabulary.

As a Berkeley native, she’s used to the nearest water being the ocean, rather than the rivers and lakes she explores in the Pacific Northwest. “I’m not used to not being by a body of water,” she says, “and so I called the river and the lake the ocean for my first two years.” At Duke, she’ll be back to the ocean, but it will be to the east, not the west.

The growth is also apparent in her maturity as a player. She’d get stuck in her head as a freshman, she says, and wouldn’t necessarily know how to get out of that mindset.

It was advice from Coach Abel that broke her out of it. “The message was that fish have six-second memories,” Freeman says. Abel told her to have the memory of a fish.

“When you make a mistake, you have to have a six-second memory,” she says. “You have to forget about it because another play is going to happen.”

Freeman says she’d also gotten more fit since coming to the UO and grown more comfortable speaking up—on and off the field. “As a goalkeeper, you see everything,” she says. It was tricky for her to call things out to her defenders at first, though, especially playing behind veterans like Croix Soto and the now-graduated Mia Palmer.

“They wanted me to talk to them,” Freeman says, “and they were able to give me the confidence in my voice to actually speak up.”

At games, Freeman’s calls of “man”—signaling the approach of an opposing player to her teammate who has the ball — and directions to organize her defense cut through the cheering in the stands. Even when the clock isn’t running, she’s there taking a knee for the national anthem—a nod to Colin Kaepernick’s protest to draw attention to systemic racism and police brutality—or checking in with her teammates.

Abel sees Freeman’s growth as a huge asset to the team as a whole. “She’s gone from being a goalkeeper to being able to be a game-winner,” he says. “She has those big moments. The big players with big personalities have big moments.”

But Rucker says you wouldn’t even know Freeman plays soccer if you talked to her. “She’s so humble about it,” Rucker says, “and will try her hardest to make sure other people around her are getting the recognition as well, even though she should be getting a lot of credit for how far this program has come.”

And those across the country are taking note. Ahead of the 2022 season, Freeman was placed on Mac Hermann trophy watch list, an award given to the country’s best men’s and women’s Division I soccer players each year. She’s made various all Pac-12 teams, joined the U.S. U-20 Women’s National Team for camps in December 2021 and May 2022 and had the opportunity to train with the National Women’s Soccer League’s Kansas City Current the summer before her junior season.

Abel says she excelled in the Current’s environment. Freeman relished the chance to experience a week of day-to-day life as a professional athlete—and to explore Kansas City alongside former UO midfielder Chardonnay Curran, who was in her rookie season with the Current. Gaining mentorship from players like U.S.Women’s National Team goalkeeper AD Franch was invaluable, Freeman says, as well as understanding the little areas where she’ll have to grow her game to make the jump to the next level. For Abel, that means looking at the areas where a goalkeeper could be exposed in a faster-paced environment, like points to decision making and “being a little bit more advanced with your feet.”

“I knew I wanted to play soccer,” Freeman says, “but I never knew what it was going to be like. Being in that environment showed me that’s something I know I will be able to do. I will be able to get to that level if I put in the work.”

Beyond making that jump, Freeman says she wants to continue to grow as a goalkeeper and learn as much as she can from her political science classes. Although the last of these is a relatively new aspiration—Freeman says she wasn’t super invested in academics until college—the first two targets reflect ambitions she’s had for much of her life.

Freeman’s proven her abilities as a goalkeeper, Callahan says, but “she’s just as incredible of a human being off the field.”

That off-the field personality shows up in Rucker’s friendship with Freeman. “She has been my biggest support system,” Rucker says. “I literally would not be alive if it wasn’t for this girl.”

Freeman has been an irreplaceable presence in Rucker’s life—and for her teammates on the field. But now Freeman has new challenges ahead of her: recovering from an offseason hip surgery, moving across the country and filling the shoes of graduating Duke goalkeeper Ruthie Jones, who helped her team to a sixth-place NCAA regular season ranking and all the way to the quarterfinals in the postseason tournament.

“It’s a change and a new beginning,” Freeman says, “and I’m so excited for that new beginning.”

This story was originally written as a profile for Eugene Weekly in fall 2022, but it never ran, as Freeman transferred before its publication.