To view this content, you must be a member of the Rose City Review Patreon

Already a qualifying Patreon member? Refresh to access this content.

Sam Coffey was drafted in 2021 by the Portland Thorns. She was the 12th pick overall from Penn State University and an attacking midfielder. In a class where Emily Fox and Trinity Rodman were selected with the first two picks, Coffey has become the absolute steal of the 2021 draft.

At the time, former head coach Mark Parsons praised Coffey’s ability to pass and score and her skill in the final third. At the draft, he described her as a “difference-maker, can pass and shoot.”

If you look at the modern game, can dribble, who can twist and turn,” he said. “We’ve lacked some of that, you know, the last couple of years.”

He also believed Coffey was pro-ready—despite the fact that she chose to take advantage of an extra COVID-19 season Penn State before joining the Thorns in 2022. “That dynamic ability was key bringing in Sam, who’s going to have an immediate impact,” Parsons said. “This is someone who can be a difference maker in the final third.”

After Angela Salem’s retirement after the Thorns’ 2021 campaign and Lindsey Horan’s loan to OL, Portland was looking at a possible rebuild in midfield heading into the 2022 season.

Thorns general manager Karina LeBlanc and then-head coach Rhian Wilkinson put on a roster-building masterclass. Enter rookie Sam Coffey and NWSL newcomer Hina Sugita. Wilkinson was brilliant to see that Coffey had a chance to be a world-class No. 6 for her squad.

In Coffey’s first season, she was named to the NWSL Best XI first team, earned four caps for the USWNT, was nominated for rookie of the year, and was crucial all season in Portland’s NWSL championship run.

The Rose City Review recently spent some time talking to Coffey about her 2022:

On keys to her immediate success at her new position and how much support she received throughout last season.

Coffey: “There were a lot of keys. One of [the] biggest ones for me is the belief of the people around me and the support of the people around me. When you’re a [No.] 6 on a team like this, they make my job a lot easier. They were so encouraging and helpful—and still are—in my development and learning of this role.

“I can’t even put into words what that feels like, and how comforting [it is] to know that I’m looking from my left to my right and seeing the class all around me. I think just having a real growth mindset with it; I’m not going to get it perfect, I’m still learning.

“I am still learning. It’s not going to be this constant uphill progression. Rhian used to always encourage me to get a PhD in this position, and I love that language, like a student. I’m just trying to learn about it every day, get better at it every day. I’m not going to have it all, all the time.

“There are going to be areas I need to improve, there are going to be bumps, just like this month has presented. Definitely a bump in the road, but I am so confident that it’ll serve and help me, make me a better player, better person, better competitor, and I’m just really excited to experience that.”

USWNT head coach Vlatko Andonovski’s roster for the 2023 SheBelieves Cup somehow managed to omit Sam Coffey from that list. Andonovski has said that he believes Coffey should be considered an NWSL MVP candidate. She was arguably the best defensive midfielder in the NWSL in 2022 and should have been a lock for the Women’s World Cup in Australia/New Zealand.

On the omission from the 2023 SheBelieves Cup and doing everything she can to make the WWC roster.

Coffey: “Obviously, I am disappointed not to be in camp, but I think this presents a really good opportunity for me to fine-tune areas of my game. Even seeing me out here with Vytas [Assistant Coach and former Portland Timber Defender], working on different areas of my game that need some refinement, like aerial challenges, 50/50 balls, being more aggressive. So, I think, I’m really viewing this time as an opportunity to address those things, but like you said it’s my dream to go.

“I want to serve and be on that team. I want to be there, and I believe I’m good enough to be there. I don’t think I need to do anything differently. I’m going to continue and try grow and be my best self. But I think taking this time reflecting and fine-tuning different areas of my game [to the] best of my ability is a good place to start. I just want to continue to be who I am, be authentic to me, just continue to grow during this process.”

If there’s extra motivation for her.

Coffey: “Yeah, I’d say I already have intense fire burning without a setback like that. Of course, it’s all motivation, all fuel for me. Again, I think it does give me an opportunity to even mentally, physically, spiritually reflect and address things that I need time to address and to watch those games. Obviously, cheer the team on, but watch it tactically, watch it from a perspective of how I can improve and how I can just stay locked in and focus on what the group’s doing.

“I would say of course it does light a fire, but I want this more than anything. I’m going to do whatever it takes to get there.”

Whether everyone likes it or not, Coffey should make the World Cup team in 2023. It would be colossal failure to have her wait until 2027.

Coffey is the best distributor in the USWNT pool, and it’s not close. She is an elite quarterback at the position and is able to keep control of the ball with her dribbling, quick thinking, turns, and world-class ability to read her opponent’s defense.

Andi Sullivan is the only other true No. 6 on the USWNT roster and is a very fine option. Still, Sullivan and Coffey are two completely different players, and it’s great to have as options depending on the matchup. Having these two players rotate at the World Cup would be the best case scenario for the USWNT.

As Andonovski continues to experiment with Taylor Kornieck at the No. 6 just months before the WWC, it’s obviously there’s not enough time for her to master a new position. It’s also very apparent that the role is not where she is most effective on the pitch.

“I don’t see her in that light for us,” San Diego Wave head coach Casey Stoney said when asked about Kornieck’s role with the national team. “I think we’d be taking away her strengths if she played as an isolated six.”

That brings us back to Coffey, who is one of the most naturally gifted No. 6s. In most cycles, she would be a lock for the USWNT—and probable starter.

Still, she’ll look to start the NWSL season off blazing hot and force Andonovski’s hand in her favor.

With a year of league play under her belt, Coffey will be trying to pad the stat sheet this season—adding to her two assists and one goal in 2022. She has already taken most of the set pieces for the club, and has continually improved.

“I think she’ll keep growing,” Thorns head coach Mike Norris said. “She’s young. She’s got the hunger and desire.”

Coffey rarely makes any mistakes, has a field vision that is utterly remarkable, and picks out difficult passes with ease. Expect her to be even sharper, more dangerous, and more influential for the Thorns in 2023—from defense and distribution to playmaking as a passer and scorer.

It’ll be a tough game for anyone trying to defend against Coffey in the NWSL this season—and hopefully we’ll be able to say the same about players going up against her on the international stage.

Before forward Lindsey Horan ran onto the field for her 105th cap with the United States women’s national team, she took a second to soak in the moment.

She surveyed the sold-out crowd at Kansas City, Kansas’, Children’s Mercy Park, draped in red, white and blue, not a single empty seat in sight. To her left stood a framed jersey that read 100. On her right was her immediate family, their words drowned out by the applause that reverberated from the south deck to the American Outlaws’ supporters section that temporarily occupied The Cauldron.

Before the game, Horan’s sports psychologist told her to take in every single moment, no matter how big or small. What came of it was an afternoon full of emotion and gratitude.

“I’ve cried about seven times today, ” Horan said.

In the hour leading up to the match, the Coloradan experienced one of the “most special moments” of her career. Forward Carli Lloyd –– about to play in her second-to-last game with the national team –– approached Horan with a jersey. On it, the number 10 sat below the name “HORAN.”

As she absorbed the scene before kickoff, Horan couldn’t help but think about what transpired in the locker room and what it took for her to arrive at that very moment.

“The players on this team are so good and the standard for this team is so high,” Horan said. “To be able to play, work, come into camp and get the opportunity to play for the national team for 100 caps is such an honor.”

Unfortunately for Horan and the USWNT, the on-field result –– a 0-0 draw against the Korea Republic –– wasn’t nearly as memorable. The team failed to win a home game for the first time in 22 attempts and it has been 60 home matches since an opponent held the USWNT scoreless on home soil.

Still, Horan provided some of the United States’ best first-half chances. In the 13th minute, her shot from outside the box deflected off the left post. Six minutes later, the Coloradan got free between defenders at the back post, but couldn’t put enough power on the cross from Kelly O’Hara to beat Korea keeper Younggeul Yoon.

“In the two years I’ve been in this job, I can’t remember that [Horan] has had a bad game or even an average one,” coach Vlatko Andonovski said. “She’s always been above average or super good. Tonight she controlled the tempo of the team, controlled the tempo of the game and had a great mindset.”

All three Thorns played heavy minutes in the USWNT’s draw Wednesday night. Horan and defender Becky Sauerbrunn both started while forward Sophia Smith subbed in in at halftime. Seven players who currently play for the Thorns or have played for the club in the past made Andonovski’s game day roster against South Korea. Some other familiar names? Tobin Heath, Emily Sonnett, Adrianna “AD” Franch and Alex Morgan.

Franch started in goal and kept a clean sheet in her first “home” game with the United States. A native of Salina, Kansas, “AD” recorded her only save in the 35th minutes to help her team secure the clean sheet.

Smith, making just her ninth appearance with the national team, entered the game right after halftime and made an immediate impact. While she didn’t find the back of the net, Smith’s runs into space resulted in dangerous attacking opportunities. When she couldn’t get in behind Korea’s defense, Smith was more than comfortable dribbling past defenders on her own, leaving them in her wake.

“Tonight was one of the first times I’ve felt like [Smith] was at her most confident,” Horan said. “That was really cool for me to see. She was driving at players, pressing, attacking. She can be so special. I’m so proud of her and I think she’s going to be a bright light on this team.”

On Wednesday night, Smith showed why she’s been a constant presence in the USWNT’s camps since the Olympics. After the game, she received a ringing endorsement from Andonovski.

“Ever since she came in there was always something happening,” Andonovski said. “Unfortunately for her, she was either a step short or she took a little too long of a touch. When all that gets corrected with more minutes and more games, she’s going to take care of that and I think she’s going to be unstoppable.”

Again, the United States’ drew 0-0 on Wednesday. But the night wasn’t just about the final result. It was about Smith finding her rhythm with the national team and Horan coming into her own as both a veteran and the next number ten on the USWNT.

“I’ve worked so hard to get to this moment and be a consistent player for this national team. Now I’m more of a vet and more of an older player. So what’s next? That was my change in mindset tonight.”

Before enlightenment: chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment: chop wood, carry water.

In 2015, Meghan Klingenberg was a standout with the US national team. At the World Cup that year, she started every game for a back line that conceded just three goals—including a Julie Ertz own goal—all tournament. She had a moment in the spotlight with a dramatic goal-line save against Sweden to rescue a clean sheet. There was no reason to suspect the 26-year-old would be on the bubble just over a year later.

But that’s exactly what happened. At the beginning of 2018, Kling was dropped for good, with little noise and less ceremony. That’s what happens when you get cut. There’s no party. One day you’re there, the next you’re not.

“It was really hard,” she remembers. “I had a lot of bitterness about it.”

The story of Kling’s break from the national team wasn’t fully told at the time. In 2016, after the Americans’ ill-fated Olympics run, she suffered a back injury, which the USWNT staff identified as a pulled muscle. In fact, it was a more severe injury that required surgery, and the misdiagnosis set her recovery timeline back significantly.

After recovering from surgery, Kling set about getting back to her 2015 form. She made a strong case for herself in the 2017 Thorns season, establishing herself as a key piece in the offense—a role she still plays today. She notched seven assists that season, the third-most in the league after Kristie Mewis and Nahomi Kawasumi; she was the only defender to record more than three. At the end of that season, the Thorns won the championship.

But she never really worked her way back into the national team conversation. From an outsider’s perspective, what’s especially baffling—insulting, frankly—is the lengths the team went to in their search for outside backs leading up to the 2019 World Cup.

Jill Ellis’s staff tried converting Sofia Huerta, a failed experiment that nonetheless prompted Huerta to move from the Red Stars to the Dash; they gave famous homophobe Jaelene Daniels (née Hinkle) a second chance after she’d refused to play in a Pride Month jersey. For their part, the stans—many of them, anyway—wanted Ali Krieger back in the picture and howled for blood every time she was left out of a lineup. We all know how the search ended: with Crystal Dunn, one of the most dangerous attacking players in the world, becoming a locked-in starter at left back.

All that happened because the foregone conclusion, before she’d even had the chance to recover fully, was that Kling’s time was over.

That was a blow. “It felt unfair to not be given a chance with the national team, knowing that I had this injury that they had misdiagnosed for a long time,” she remembers. It’s one thing to get fired because you messed up; it’s another to get punished for someone else’s mistake.

“I could not find joy in the game. I was just playing to get back to where I was.”

Zen master Dongshan Liangjie of Mount Dong said to the assembly, “Experience going beyond Buddha and say a word.”

A monastic asked him, “What is saying a word?”

Dongshan said, “When you say a word, you don’t hear it.”

The monastic said, “Do you hear it?”

Dongshan said, “When I am not speaking, I hear it.”

But that was then. Times have changed.

“I guess the only way that I can put it is that the past doesn’t exist, and the future isn’t real.”

I’m talking to Kling in the stands at Providence Park on a warm day in August. We both have masks on; hers is gray plaid with a Pittsburgh Steelers logo. 2015 was a lifetime ago. Longer—a different plane of existence. The whole Trump administration sits between now and then.

“All we have right now,” she continues, “is this moment right here in front of us. And we get to choose what we want to do with it. If we want to be distracted and not be here, present, we can choose to do that… I think when we choose presence, a lot of other things happen because of that.”

For Kling, this wasn’t an easy lesson to learn. It’s not a mindset that comes easily to professional athletes, for whom performance matters, and hypercompetitiveness is a job requirement. But excellence is paradoxical: the more you fixate on results—on the free kick you whiffed or the bad day you had in training—the less you focus on the process of getting the results. A focus on winning turns into a fear of losing. That fear plagued her, even as she remained a key player for the Thorns through 2018 and 2019.

“I was one of the most outcome-driven athletes that you could find, before I had this kind of paradigm shift,” she says. “And it just wasn’t working for me anymore. I was having all kinds of anxiety, three quarters of a month. I was having trouble physically breathing, because I was having so much anxiety about how I’m going to play, how I’m going to do, what happened last game, all these different things.”

In early 2020, something snapped. “I was just like, so tired,” Kling remembers, “of having anxiety all the time, worrying about the next game. My body would get tight when I’d play, then I’d relax for a few days, and then it would build, build, build. It was like, 10 years of that.”

Through a friend, she got in touch with a performance coach named Jason Goldsmith, whose core philosophy is to teach athletes to focus on the things they can control and let go of the things they can’t. “[Whether] you win or lose, or if you play well, or statistically do well, all of those things, you know, are not something that’s controllable,” Goldsmith says.

Even the best players in the world miss tackles and hoof shots over the bar. As a defender, sometimes you can save the day, and other times you have to go one-on-one against Lynn Williams. “What is controllable,” Goldsmith says, “is, how do you feel when you are playing?”

One tool he uses with athletes is a biofeedback device called a FocusBand, a wearable EEG that connects to a smart phone and allows the user to directly monitor their brain activity. “The benefit of having something like that,” he explains, “that gives you direct feedback, [is that it] allows you to explore different meditation practices in a way that you can see, ‘oh, when I do this, when I focus on this, this is how it’s affecting my brainwave frequency. Or if I do this, this really doesn’t work.’”

In Taoism and Zen Buddhism, one goal of meditation is to enter a state of mushin, or “no-mindedness.” It’s a state of complete engagement in an activity—whether that activity is meditating or kicking a soccer ball—without thought or judgment.

“If you had the device on and you were thinking about how to play,” Goldsmith explains, “you’re no longer playing.”

That state of mind, sometimes called “flow,” is an indispensable tool for athletes, or anyone doing a high-skill task that requires intense concentration. It also has a neural fingerprint that the FocusBand can pick up on. For Kling, Goldsmith sewed the device into a hat, so she could wear it throughout the day. Using the band as part of a daily mindfulness practice, she transformed her outlook.

“Sometimes we go to the grocery store, right,” she explains, “and we’re standing in lines waiting. But what are we waiting for? We’re waiting for the future.” The future, though—as we’ve already discussed—doesn’t exist. At some point, Kling realized, “I don’t need to wait. I can just be.”

That shift helped her reconceptualize the game of soccer. “When I first got [to Portland], it was all about outcomes. How do I make 100% passing, how do I create the most chances? How do I stop the most one-v-ones, all these different things. And I would just data myself to death.”

By shifting her focus away from outcomes, Kling says, “everything slowed down.” Instead of thinking about completing passes or chances, or winning the ball back in specific moments, “I just think about it in terms of space. How do I get my body and this ball into this area? Instead of seeing defenders running at me, or where my players are running, I more see everything at once.”

The excellence paradox works in reverse, too. Not worrying about the numbers has enabled Kling to improve her numbers. So far this season, she has a 78.5% pass completion rate, about 5% more than she had in 2019, a 43.9% long pass completion rate—a 10% improvement—and is attempting about 57 passes per game, compared to 43 in 2019.

“For [Dōgen], each moment of practice encompasses enlightenment, and each moment of enlightenment encompasses practice. In other words, practice and enlightenment—process and goal—are inseparable. The circle of practice is complete even at the beginning. This circle of practice-enlightenment is renewed moment after moment.”

–Kazuaki Tanahashi, Enlightenment Unfolds

Kling’s journey over the last three years parallels that of the Thorns as a team. “[In] ‘16 and ‘17, we were very, very focused on the process,” Mark Parsons says. What he means by “process” is a relentless focus on getting better as a group, according to an abstract vision of the kind of team they want to be, rather than numbers of wins and losses. Train well, work hard, strive for improvement, and the results will follow, the reasoning goes. “‘18, ‘19, I think we got—I got—distracted with the outcome,” he says.

It sounds a little absurd to say there was something wrong with a team’s approach in two seasons when they went to the league championship and the playoff semifinal, respectively, but within the team, something had soured. The Thorns want and expect to be the best, and with their resources, there’s little excuse not to be.

From the outside, nothing seemed particularly amiss during that time. You had to know what to look for: a player reporting late for uncertain reasons, a vague disjointedness and a whiff of frustration in the attack. The team’s culture issues came to a head at the 2019 semifinal at Chicago, when Caitlin Foord, Midge Purce, and Hayley Raso started on the bench. After the 1–0 loss, AD Franch alluded to internal fracture, saying the team needed to “regroup, find our culture, and get back to who we are.”

Some of that was a personnel issue; too many players, regardless of quality, weren’t bought into Parsons’s vision for the team. The club cleaned house over the offseason and brought in the likes of Rocky Rodríguez, Sophia Smith, and Morgan Weaver. At least as important was that the coaching staff took a long look in the mirror and realized they’d strayed from their core values.

Effort is the first of those values. But that’s hardly unique, either when looking to Parsons teams of past years—if I had a nickel for every time I’d recorded him talking about “maximum effort,” I’d have, well, quite a few nickels—or when you think about the whole edifice of team sports, especially in this country.

What’s new for this version of the Thorns is the striking literalness with which they apply their stated values. You don’t have to speak with anyone on the team to know this; you can see it on the field. They want to improve at one specific style of play, so they use the same basic game plan every week, regardless of personnel.

Most teams, including the Portland of two or three years ago, line up different ways in different situations, moving to a back three or employing a different pressing scheme to fill in the gaps when certain players weren’t available. Now there is one plan, with clearly defined roles at every position, which every player on the roster knows like the back of their hand.

The goal is to win. But they see winning as a long-term goal, not an immediate one. Winning this week is one thing. They want to win the league.

“If we live the rollercoaster of winning and losing and tying with the ball going in or the ball not going in,” Parsons says, “we’re just a team that defines ourselves by outcome. But medium- and long-term success isn’t decided by outcome. It’s about improvement.” Control the controllables, and the rest will fall into place.

Parsons and Kling both use the 2020 Challenge Cup as an illustration.

“We went into the COVID Cup in 2020 and came in last in the preliminary stages,” Kling says. “But that’s because we were so beholden to our mission, we were so beholden to the process, that we were not going to change what we were going to do just to get results. I know that really bothered a lot of people, but it didn’t bother us.”

“We all knew we were on a different journey,” Parsons says.

When Buddha was in Grdhrakuta mountain he turned a flower in his fingers and held it before his listeners. Every one was silent. Only Maha-Kashapa smiled at this revelation, although he tried to control the lines of his face.

Buddha said: “I have the eye of the true teaching, the heart of Nirvana, the true aspect of non-form, and the ineffable stride of Dharma. It is not expressed by words, but especially transmitted beyond teaching. This teaching I have given to Maha-Kashapa.

“I had to realize that life wasn’t fair,” Kling says.

Unfairness—along with pain, loss, and regret—are inevitable. What we can change is how we react. In Buddhism, the cause of suffering is not what happens to us, but the way we push back internally against it. You can be bitter forever, or you can learn to let go.

The idea of getting back to where she was—back to her 2015 form, back to the national team—took some time for Kling to let go of. “But,” she says now, “there’s no getting back to where I was, and why would I want to anyway? Why would I want to go back in the past when I could take all of that information and use it now, and be a totally different player, be a player that I want to be?”

Arguably, she’s better now than she was then. She’s having the club season of her career. More important, she’s found joy in the game again. As she said in a press conference during the 2021 Challenge Cup, “I’m literally having a fucking blast right now.”

“I’ll tell [friends and family] stories that happened in practice,” she says, “and they’re like, ‘do you ever practice? All I hear about is you laughing, all I hear about is you telling these crazy-ass stories!’ And I’m like, ‘yeah, well, we do that the entire practice. All I do is laugh and play hard, the whole practice.’ I love that, because to me, joy is one of the main drivers of me getting better. When I’m laughing and having fun with my friends, I know that I’m fully tuned in to exactly what we’re doing.”

She sees the pressure, the anxiety, the feelings of inadequacy she long struggled with in other elite athletes. It’s getting more common for athletes, many of them women—Naomi Osaka, Simone Biles, Christen Press—to pull out of competitions for mental and emotional injuries in addition to physical ones.

Those injuries are complex and often rooted in off-field trauma, but to the extent that competition itself exacerbates them, Kling says, “I personally feel like we’ve let these women down. We never taught them that competition should be joyful. We never taught them to be just content with exactly who [they] are.”

“All I want for them is to be able to step up onto the biggest stage of their lives, knowing that they have done everything that they can possibly do to get to that moment, and enjoy it.”

We’re in quarantine. Sports are on hold indefinitely. I don’t know about the rest of y’all, but I’m getting tired of watching a ridiculous amount of Degrassi: The Next Generation—a show I chose purely because it has almost 400 episodes—in between pretending to do work for my online classes. So what else is there?

Watching old soccer games? Can be fun, but if you’re like me, you have a hard time focusing for an hour and a half on a sports match you’ve already seen. (Especially if you end up thinking about the current lack of sports and feeling sad about that instead.)

Books? Sure. I recently finished There There, which I definitely recommend checking out if you haven’t yet. I’m now working my way through a book about consciousness and octopuses—maybe more on that in a week or two. The thing is, I can only spend so much time reading every day, so that can’t be the only thing in my life.

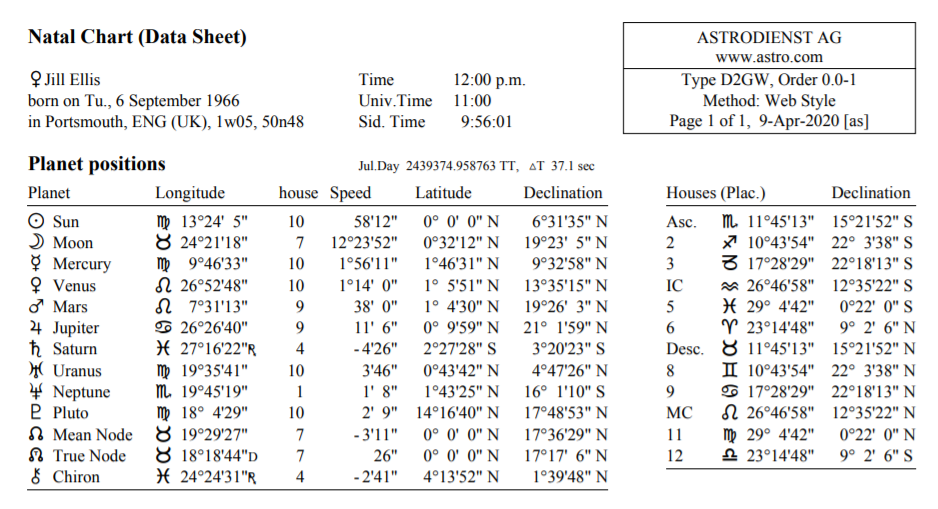

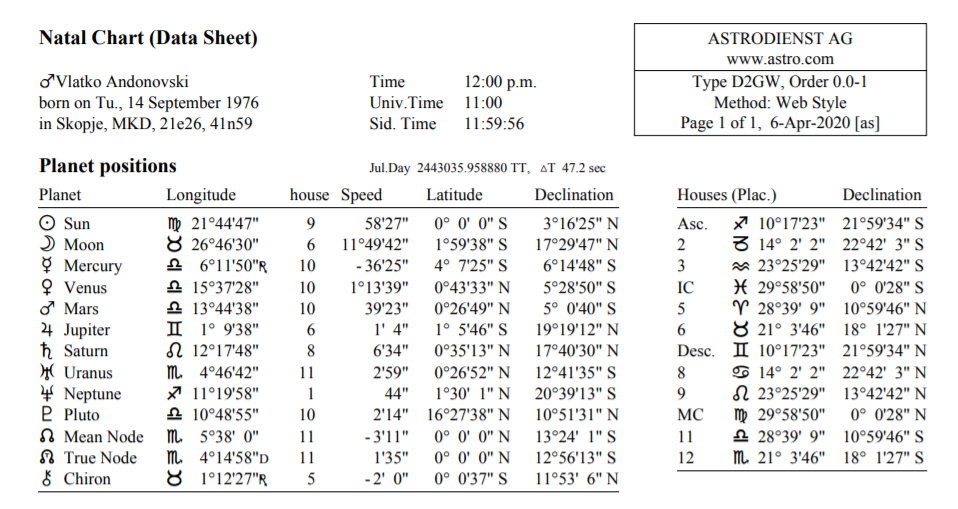

Astrology? Now we’re onto something. I started a comparison between Jill Ellis’s and Vlatko Andonovski’s charts a couple months ago out of curiosity; I wanted to know what the stars had to say about their different coaching styles and appearances in the eyes of fans. While I never fully put anything together then, now seems like the perfect time to change that.

At its most basic level, astrology is about planets, signs, and houses. These are usually explained in terms of energy. Planets identify what energy is being dealt with—for instance, the sun describes one’s most basic self, while Mercury is about intellect and communication. Signs explain how that energy manifests itself, and houses express the areas of life in which that energy appears. For the purposes of this piece, I’m looking just at the first two, as the placement of houses changes every two hours and I don’t know Ellis’s or Andonovski’s exact time of birth. I’m also focusing on the inner, “personal,” planets, those which reflect on one’s individual personality.

As mentioned above, one’s sun sign describes their most fundamental self. It’s the one we talk about when discussing astrology more generally—you’re usually an Aries if you’re born between March 21 and April 20, a Taurus from April 21 to May 20, and so on. In both Ellis’s and Andonovski’s cases, the sun falls in Virgo.

First and foremost, Virgos are analytical, always evaluating and fine-tuning details. Industrious and pragmatic, this placement bodes well for someone who coaches soccer at its highest level; it lends itself to a technical and tactically creative read of the game. We can see this in Ellis’s array of experimental formations and in Andonovski’s willingness to adapt his game plan in accordance with the strengths and weaknesses of the opponent. The stereotypical Virgo trait of attention to detail is relevant here as well; it speaks to both these coaches’ drive for constant improvement.

Moving down their charts, both coaches’ signs again align, as they both have moons in Taurus. While the sun represents one’s most basic identity, the moon turns this focus inwards to emotions and the subconscious self. Taurus is represented by the bull; it centers around stability and dependability. This placement tells us that Ellis and Andonovski are fundamentally nurturing people who are in control of their emotions.

As alluded to earlier, Mercury placements tell us about thinking and communication. For Ellis, this planet is again in Virgo, focused on practicality and logic. We see this in her trial-and-error approach when it comes to lineups—the infamous Allie Long in the center of a three-back experiment comes to mind. However, Ellis’s reason-based method of thinking also has its clear advantages, most notably when she outcoached Phil Neville’s England side in the 2019 World Cup semifinal. (Neville is an Aquarius, Capricorn Mercury, if you were wondering.)

Andonovski’s Mercury falls in Libra. Symbolized by a set of scales, Libra is about diplomacy and balance. This manifests itself in the way Andonovski manages his teams—he emphasized that the Reign FC squad was a family throughout the 2019 season, a clear indication of his value of unity. The Libra trait of conflict avoidance is also evident in Andonovski’s coaching; he tends to avoid direct play in favor of building through cohesive teamwork and picking the moments to strike.

Venus tells us about relationships—romantic or otherwise—and creativity. Libra is again present for Andonovski here. In this case, his chart tells us that he’s easy to get along with, something supported by the seemingly unanimous praise we hear from his players. Libra Venuses also thrive when expressing their imagination; Andonovski’s love of the game shines through in his meticulous research and tactically adaptable style of coaching.

In contrast, Ellis’ Venus is located in Leo, a sign associated with loyalty, pride, and radiance. Those with this placement are often charismatic in interpersonal relationships and crave admiration. Additionally, Leo Venuses are more likely to possess extravagant material belongings—or in Ellis’ case, to have peacocks basically living in her yard.

Leo also appears in Mars on Ellis’ chart. The planet tied to physical drive and initiative, a Leo Mars often indicates a visionary nature. This tends to make one a good leader, so long as their ego doesn’t get in the way. In Ellis’ case, this allowed her to confidently lead the USWNT for a number of years, although a conflict between pride and the humbling detail-oriented nature of her sun and Mercury could have led to thoroughness in some areas and an overconfident lack of oversight in others.

Like the other two inner planets, Andonovski’s Mars is in Libra. When three planets—or four, depending on who you ask—fall in the same sign or house, the energy described by that placement is often enhanced. (This is called a stellium.)

Libra Mars leads to the channeling of energy into intellectual or artistic pursuits. Whereas Mars often describes impulsive action, those with Libra placements are often more measured; they tend to consider all sides before making a decision. For Andonovski, this only accentuates his strengths as a coach. He is decisive, but not without ignoring reason.

Ellis exited the job of USWNT head coach boasting a 106-7-19 record and two World Cups, numbers that make it hard to dispute her success. While of course this isn’t fully due to her star chart, and of course the circumstances of one’s birth aren’t the sole indicator of whether or not one will be a good coach, Ellis’s placements lend themselves to confidence and intelligence in her work. While the same signs do not appear in all areas of Andonovski’s chart, that he and Ellis share sun and moon signs indicate that the calm analysis of Ellis’s coaching will not be lost. And a little more emphasis on teamwork never hurt anyone.

Ed. note: this story was intended for publication in October 2019. Due to the vagaries of the media business, it never saw the light of day. We hope you’ll enjoy it as you practice social distancing.

France 2019 will be remembered as a big moment for women’s soccer, I think. In its wake, NWSL attendance experienced what looks—tentatively—more like a rising tide than a wave. In Europe, it catalyzed record sponsorships for clubs and leagues. The hype around it is part of what pushed longtime holdouts from the women’s game, including Real Madrid, to throw their hats in the ring. What’s going to be forgotten—what’s always forgotten about World Cups, on either side of the gender divide—is how much of the competition was brutally sad.

Inequality shapes everything about our world, so of course it also shapes the world’s game, much as we like to believe soccer is a sport that rewards talent, nerve, and perseverance above all. The mythos of the sport says that it only takes a ball to play, and that its heroes come from slums and favelas and banlieues.

And all that—it’s not not true, exactly. Fara Williams really was homeless for six years as a teenager. Nadia Nadim really did learn to play soccer while living in a refugee camp. We love those stories, both because they’re inspiring and because they let us believe soccer exists on a more egalitarian and meritocratic plane of being than ordinary life does.

But at a World Cup, where the teams competing run such a complete gamut from good to bad, rich to poor, the truth comes out. Inequality defines the competition. It’s rarely said directly, because it’s not a nice thing to say, but the majority of the field is always teams that stand literally no chance of winning.

As in every other facet of life, the gap between the haves and the have-nots is bigger on the women’s side than on the men’s side. Plenty has been written on the subject of the massive and universal underinvestment in the women’s game, so rather than repeating any of that, I will simply say that the spectacle of this sport is something I find increasingly hard to participate in.

The social media zeitgeist takes on a specific tone any time there’s a particularly wild game, every tweet screaming “WHAT IS HAPPENING???” and “OH SHIIIIIT!!” I get that this is fun, and I genuinely take no enjoyment in pointing out that too often, at the World Cup, those moments involve teams beset with dysfunction. Australia-Brazil, which ended 3-2, was one such game—Australia, which fired its head coach less than six months before the tournament, edging out Brazil, whose federation has always chosen to pin its hopes on Marta rather than actually investing in the women’s game. The generational talents who have been let down by this sport’s power structures are far too many to name here.

I could try to list all the other times this tournament broke my heart: the time France got to retake a penalty because VAR ruled that Nigeria’s keeper came off her line a fraction of a second early, and won the game as a result. The time Argentina, the worst-supported team in the tournament, came back from a three-goal deficit against Scotland only to have their hopes at a win—which would have sent them to the knockout stage—dashed when the referee cut stoppage time short.

But there is one moment that serves as the tragic, surreal nadir of the whole thing: Cameroon-England.

The social contract in sport rests on the mandate that losers must lose gracefully. So when things didn’t go Cameroon’s way against England, their reaction—not just complaining, but raging, crying, fouling left and right, looking like they were about to either start a fight or walk off the field—was more shocking than an upset win would have been.

It was the most bizarre spectacle to have taken place on a soccer field in recent memory, and the English press, especially, was eager to decry it as “DISGRACEFUL” and “SHAMEFUL.” The fact that the perpetrators were women no doubt worsened the shock to delicate sensibilities.

Taking a step back and thinking about the gargantuan disparity between these two soccer teams, though, you almost have to wonder that such displays aren’t more common. England is a team of professionals who play in a competitive league that recently received a £10 million sponsorship from Barclay’s. Meanwhile, the top-tier competition in Cameroon is one that has been described by Cameroonian journalist Njie Enow as “an underfunded domestic championship staged in appalling conditions.” These two teams compete under a common set of rules, but that’s the only parity that exists between them.

And as it does everywhere, sexism amplifies such inequality. Every women’s team is underfunded compared with their male counterparts. Federations spend money on the men hoping that investment will bring success, while women’s teams aren’t even noticed until they start winning—if they’re given a chance to play at all.

What Cameroon did was not sportsmanlike—but one effect of sportsmanship is to provide a glossy cover for the profound unfairness that shapes our world. At some point, we have to look in the mirror and ask why we value the appearance of cooperation and equality more than the conditions of players’ lives—more, in other words, than actual cooperation and equality.

It is at least counterintuitive, and perhaps simply hypocritical of me, to use that moment, the spiritual low point of the World Cup, as framing for what came next.

Heading into the tournament, I did not know how I was going to feel about the US women, the team that, once upon a time, made me fall in love with this sport. The CONCACAF qualifying tournament back in October was an even bleaker showcase of inequality than the group stage of the World Cup, and if the USWNT’s utter dominance in women’s soccer wasn’t embarrassing enough, you may have noticed that this is not an era when it feels particularly good to be an American.

And then, come the knockout rounds, I found myself rooting for them—not resignedly or out of some sense of obligation, but really, from the depths of my heart, wanting this team to win.

If there’s one strictly soccer-related lesson from France 2019, it’s that the US remains, and likely will remain for some time, the best women’s soccer team in the world. It is not close. They had by far the most challenging schedule of any team, and hardly broke a sweat as they beat both France and England. None of the other supposed contenders—Australia, Germany, Japan—ever looked like possible world champions. There should never have been a question that the US was going to repeat their 2015 victory.

All this, of course, epitomizes the unfairness I spent the first half of this essay detailing. We live in the richest and most powerful country on earth, and our women’s national team is the best-supported in the world. We are Goliath and everyone else is David.

But the reason for that huge disparity doesn’t boil down to a simple question of GDP. Of course it does have to do with that, but it also has to do with the fact that 50 years ago, this country did one small thing right for American women, in passing Title IX, which made it normal for girls to play soccer at a time when that was illegal in many traditional footballing countries.

In simply giving girls the opportunity to play sports, this law converted our huge population into a huge player pool, something you can still see in the USWNT’s incomparable depth: the 2019 roster comfortably contains two full lineups that would be in the top five in the world. That says something about who we are as a country, or at least who we aspire to be. I have never had a lot of patriotic feelings, but I’m proud of that.

Somewhere in the multiverse, there’s a version of earth where women’s soccer is just as popular as men’s, where poverty doesn’t exist, where people can live how they want to live and be who they want to be regardless of where they were born, what they look like, who they love. We do not live in that world. We live in a world where the president of the most powerful country on earth has openly bragged about committing sexual assault.

And in this world, the US women’s national team—the whole institution, but especially this particular US women’s national team—is a rare and special thing. It’s a comfort.

Earlier, I wrote that soccer doesn’t exist on some higher plane where injustice vanishes—and our women’s national team is subject to the coarse vulgarity of sexism and homophobia and racism and everything else. But watching them win the World Cup, it felt like they were above all that.

The 2019 USWNT was the best, on the field, that they have ever been, and I hope it’s not too corny of me to say they were the best off the field, too.

That clip of Megan Rapinoe saying she wasn’t going to the fucking White House? That clip was a month old by the time it blew up on social media. We should never have been talking about it. But so help me, I liked it. The virality of that moment was intentional, and not in a way that benefitted her or her teammates—but she handled it with remarkable grace and composure.

For the first time in their history, this team was not concerned with projecting an image of family-friendly wholesomeness. They swore in public and celebrated with abandon. They were, as a group, incredibly gay. What they projected, instead of the traditional dumbed-down, for-all-the-little-girls-out-there image, was one of strength and outspokenness and pride, as 23 women who play soccer.

And whatever base stupidity anyone tried to level at them simply bounced off, because they won, and did it in an absolutely clear and irreproachable fashion. Win like that, and you’re untouchable. All the nonsense about the goal celebrations, all memory of our idiot president tweeting at Rapinoe, faded into background noise as they sprayed Budweiser on each other and yelled “I’ma knock the pussy out like fight night!” in unison (it’s a Migos song).

This is the paradox sports present us with. They exist firmly in our mercilessly unfair reality, but at their best, they involve a suspension of disbelief that lets us forget that reality. I hope, without much optimism, that by the next World Cup, our reality might be a little less unfair. But even if it’s not, this tournament is the kind of space that’s much too rare—one where sometimes, good guys win.